Iron screens (rejas) became ubiquitous in the architecture of post-war Puerto Rico due to the security they provided and their ability to allow for cross ventilation. Today, theses iron rejas are not only viewed as a protection device as much as a language that pertains to the island’s visual culture. Graft alludes to the aesthetic, decorative and nostalgic qualities of these iron fences by transplanting its representation to structures in the US.

A take-away publication is the literary component that complements this project. Bilingual essays, in which writers from a variety of disciplines, such as art history, art, architecture and politics amongst other fields, reflect on rejas in the contexts of their individual fields of expertise.

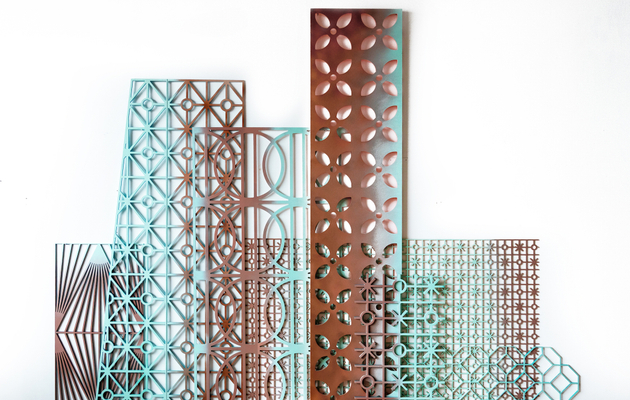

Poet, playwright, and Nobel laureate Derek Walcott, a native of Trinidad and Saint Lucia, asserted in 2002 that, "the strength and beauty that will begin to be unique in Antillean architecture is in its individual genius, in the impulse to be elaborate in a flourish, to convey our light and a lightness of heart." This decorative bravura comes across in the 2009 book La Ciudad de los Balcones, in which Edwin R. Quiles Rodriguez and Consuelo Gotay display, describe, and diagram examples of the distinctive Creole-style family homes of the Villa Palmeras area of San Juan, Puerto Rico. Quiles relates that the "shotgun" layout of these working-class residences was adapted from the Yoruba dwellings of African slaves, which was developed in Haiti and then migrated abroad with hacienda owners after the slaves revolted. The term balcon describes the indoor-outdoor porch spaces that proliferate throughout the island, and are fenced off by ironwork grills known as rejas, whose intricate patterns recall Arabic mosaic designs. In wooden form, these rejas are the foundation of Edra Soto's GRAFT project-- although a wooden reja also appears on the Casa Blanca, the centuries-old house of Puerto Rico's governor.

Even more than colonial and modern styles, vernacular architecture shows the full breadth of the island's historical influences, from before, during, and after colonialism. Appropriating the mesmerizing designs of rejas and transposing them on to structures in the mainland U.S. provokes questions. Can a nation that has so freely appropriated the land and resources of Puerto Rico, while consigning its residents to second-class citizenship and exorbitant government debt, be itself appropriated as a screen upon which Soto can project the (wooden) screens of her Boricua childhood? Or does the gesture become a multiculturalist token of assimilation, an exotic garnish that helps to erase the trauma of conquest, exploitation, and slavery? Can such an appealing but unobtrusive architectural element even register with the average American viewer as an intervention at all? Learning not only the elements of Caribbean architectural style, but learning to read all buildings as indices of complex and contentious histories, can offer a great deal to laypeople viewing the exhibition. And, through this publication as well as through the installation, GRAFT can suggest new interdisciplinary conversations for enthusiasts and experts both within and outside architecture.

- Albert Stabler

Former iterations of GRAFT:

GRAFT | Museum of Contemporary Photography

GRAFT ( CUBA) | Smart Museum, University of Chicago

GRAFT | Chicago Cultural Alliance

GRAFT | Poetry Foundation